Topic 3 Review Questions Demand Supply and Prices Answer Key

Affiliate three. Demand and Supply

3.1 Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium in Markets for Goods and Services

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain need, quantity demanded, and the law of demand

- Identify a demand bend and a supply bend

- Explain supply, quantity supply, and the constabulary of supply

- Explain equilibrium, equilibrium toll, and equilibrium quantity

Beginning let'due south get-go focus on what economists hateful past demand, what they mean by supply, and then how demand and supply collaborate in a market.

Demand for Goods and Services

Economists apply the term demand to refer to the amount of some good or service consumers are willing and able to purchase at each price. Demand is based on needs and wants—a consumer may exist able to differentiate between a need and a want, just from an economist'southward perspective they are the aforementioned thing. Demand is likewise based on ability to pay. If you cannot pay for it, you have no constructive demand.

What a buyer pays for a unit of the specific skillful or service is called toll. The total number of units purchased at that cost is called the quantity demanded. A rising in cost of a practiced or service nigh e'er decreases the quantity demanded of that good or service. Conversely, a fall in cost will increase the quantity demanded. When the price of a gallon of gasoline goes up, for example, people look for ways to reduce their consumption by combining several errands, commuting by carpool or mass transit, or taking weekend or vacation trips closer to dwelling. Economists call this inverse relationship betwixt price and quantity demanded the law of demand. The law of demand assumes that all other variables that impact demand (to be explained in the next module) are held constant.

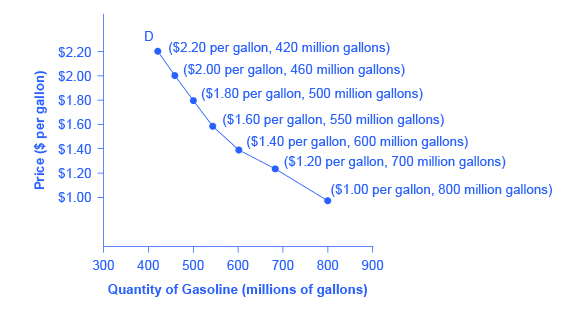

An example from the market for gasoline can exist shown in the form of a table or a graph. A table that shows the quantity demanded at each price, such as Table 1, is called a demand schedule. Toll in this example is measured in dollars per gallon of gasoline. The quantity demanded is measured in millions of gallons over some time menstruum (for example, per day or per yr) and over some geographic area (similar a state or a land). A demand curve shows the relationship between toll and quantity demanded on a graph like Figure 1, with quantity on the horizontal axis and the price per gallon on the vertical axis. (Note that this is an exception to the normal rule in mathematics that the independent variable (x) goes on the horizontal axis and the dependent variable (y) goes on the vertical. Economics is not math.)

The need schedule shown by Table 1 and the demand curve shown past the graph in Effigy 1 are ii ways of describing the same relationship betwixt cost and quantity demanded.

| Toll (per gallon) | Quantity Demanded (millions of gallons) |

|---|---|

| $1.00 | 800 |

| $ane.20 | 700 |

| $1.40 | 600 |

| $1.60 | 550 |

| $1.eighty | 500 |

| $2.00 | 460 |

| $2.20 | 420 |

| Table i. Price and Quantity Demanded of Gasoline | |

Demand curves will announced somewhat different for each product. They may announced relatively steep or flat, or they may be direct or curved. Nearly all need curves share the central similarity that they slope down from left to correct. So need curves embody the law of need: Every bit the cost increases, the quantity demanded decreases, and conversely, every bit the cost decreases, the quantity demanded increases.

Confused about these dissimilar types of need? Read the next Clear It Up feature.

Is demand the aforementioned as quantity demanded?

In economic terminology, demand is not the same equally quantity demanded. When economists talk about demand, they mean the relationship between a range of prices and the quantities demanded at those prices, as illustrated by a need curve or a need schedule. When economists talk virtually quantity demanded, they hateful only a certain indicate on the demand curve, or ane quantity on the demand schedule. In short, demand refers to the bend and quantity demanded refers to the (specific) point on the curve.

Supply of Appurtenances and Services

When economists talk about supply, they mean the amount of some adept or service a producer is willing to supply at each price. Toll is what the producer receives for selling i unit of a good or service. A rise in cost almost ever leads to an increase in the quantity supplied of that good or service, while a fall in price volition decrease the quantity supplied. When the toll of gasoline rises, for example, it encourages profit-seeking firms to take several actions: expand exploration for oil reserves; drill for more oil; invest in more pipelines and oil tankers to bring the oil to plants where information technology can be refined into gasoline; build new oil refineries; purchase additional pipelines and trucks to ship the gasoline to gas stations; and open more gas stations or continue existing gas stations open longer hours. Economists call this positive relationship between toll and quantity supplied—that a higher price leads to a higher quantity supplied and a lower price leads to a lower quantity supplied—the police of supply. The law of supply assumes that all other variables that bear upon supply (to be explained in the adjacent module) are held constant.

Still unsure about the different types of supply? See the following Clear It Up feature.

Is supply the same as quantity supplied?

In economic terminology, supply is not the same every bit quantity supplied. When economists refer to supply, they hateful the human relationship betwixt a range of prices and the quantities supplied at those prices, a human relationship that can be illustrated with a supply curve or a supply schedule. When economists refer to quantity supplied, they mean only a certain signal on the supply curve, or one quantity on the supply schedule. In brusk, supply refers to the curve and quantity supplied refers to the (specific) indicate on the curve.

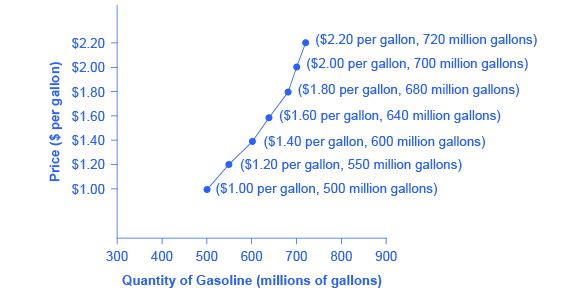

Figure 2 illustrates the constabulary of supply, again using the market for gasoline as an case. Like demand, supply tin can be illustrated using a table or a graph. A supply schedule is a table, like Table 2, that shows the quantity supplied at a range of different prices. Once more, price is measured in dollars per gallon of gasoline and quantity supplied is measured in millions of gallons. A supply curve is a graphic illustration of the relationship between price, shown on the vertical axis, and quantity, shown on the horizontal axis. The supply schedule and the supply curve are just ii different means of showing the same information. Notice that the horizontal and vertical axes on the graph for the supply bend are the same as for the need bend.

| Price (per gallon) | Quantity Supplied (millions of gallons) |

|---|---|

| $1.00 | 500 |

| $ane.20 | 550 |

| $1.40 | 600 |

| $ane.60 | 640 |

| $1.80 | 680 |

| $ii.00 | 700 |

| $2.20 | 720 |

| Table 2. Price and Supply of Gasoline | |

The shape of supply curves volition vary somewhat co-ordinate to the product: steeper, flatter, straighter, or curved. Nearly all supply curves, however, share a basic similarity: they slope up from left to right and illustrate the law of supply: as the price rises, say, from $i.00 per gallon to $2.20 per gallon, the quantity supplied increases from 500 gallons to 720 gallons. Conversely, as the price falls, the quantity supplied decreases.

Equilibrium—Where Demand and Supply Intersect

Because the graphs for demand and supply curves both accept price on the vertical centrality and quantity on the horizontal axis, the demand curve and supply bend for a particular good or service can appear on the same graph. Together, need and supply determine the cost and the quantity that will exist bought and sold in a market.

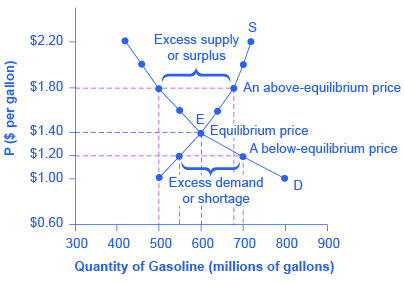

Figure iii illustrates the interaction of demand and supply in the marketplace for gasoline. The demand bend (D) is identical to Figure 1. The supply bend (S) is identical to Figure 2. Table 3 contains the aforementioned information in tabular form.

| Price (per gallon) | Quantity demanded (millions of gallons) | Quantity supplied (millions of gallons) |

|---|---|---|

| $i.00 | 800 | 500 |

| $1.20 | 700 | 550 |

| $1.40 | 600 | 600 |

| $1.lx | 550 | 640 |

| $1.80 | 500 | 680 |

| $2.00 | 460 | 700 |

| $ii.twenty | 420 | 720 |

| Table 3. Toll, Quantity Demanded, and Quantity Supplied | ||

Call back this: When two lines on a diagram cantankerous, this intersection usually means something. The signal where the supply curve (S) and the need bend (D) cross, designated by point East in Figure 3, is called the equilibrium. The equilibrium price is the only price where the plans of consumers and the plans of producers agree—that is, where the amount of the product consumers desire to buy (quantity demanded) is equal to the amount producers want to sell (quantity supplied). This mutual quantity is called the equilibrium quantity. At any other cost, the quantity demanded does non equal the quantity supplied, and so the market is not in equilibrium at that toll.

In Figure three, the equilibrium toll is $1.40 per gallon of gasoline and the equilibrium quantity is 600 million gallons. If you had only the demand and supply schedules, and not the graph, you could find the equilibrium by looking for the cost level on the tables where the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied are equal.

The give-and-take "equilibrium" means "balance." If a marketplace is at its equilibrium price and quantity, then information technology has no reason to move away from that point. Withal, if a market is not at equilibrium, then economic pressures arise to motility the market toward the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity.

Imagine, for example, that the cost of a gallon of gasoline was above the equilibrium price—that is, instead of $ane.40 per gallon, the price is $i.lxxx per gallon. This above-equilibrium price is illustrated by the dashed horizontal line at the price of $1.fourscore in Figure 3. At this higher price, the quantity demanded drops from 600 to 500. This reject in quantity reflects how consumers react to the higher toll by finding ways to apply less gasoline.

Moreover, at this higher price of $one.lxxx, the quantity of gasoline supplied rises from the 600 to 680, as the higher price makes it more than profitable for gasoline producers to expand their output. Now, consider how quantity demanded and quantity supplied are related at this above-equilibrium price. Quantity demanded has fallen to 500 gallons, while quantity supplied has risen to 680 gallons. In fact, at any above-equilibrium price, the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded. We call this an excess supply or a surplus.

With a surplus, gasoline accumulates at gas stations, in tanker trucks, in pipelines, and at oil refineries. This accumulation puts pressure on gasoline sellers. If a surplus remains unsold, those firms involved in making and selling gasoline are not receiving enough cash to pay their workers and to embrace their expenses. In this situation, some producers and sellers will want to cut prices, because it is better to sell at a lower price than not to sell at all. In one case some sellers start cut prices, others will follow to avoid losing sales. These cost reductions in turn volition stimulate a higher quantity demanded. Then, if the cost is above the equilibrium level, incentives built into the construction of demand and supply volition create pressures for the price to fall toward the equilibrium.

Now suppose that the price is beneath its equilibrium level at $i.twenty per gallon, equally the dashed horizontal line at this price in Figure iii shows. At this lower cost, the quantity demanded increases from 600 to 700 as drivers take longer trips, spend more than minutes warming up the car in the driveway in wintertime, terminate sharing rides to work, and buy larger cars that get fewer miles to the gallon. However, the below-equilibrium cost reduces gasoline producers' incentives to produce and sell gasoline, and the quantity supplied falls from 600 to 550.

When the cost is below equilibrium, there is excess demand, or a shortage—that is, at the given price the quantity demanded, which has been stimulated by the lower price, now exceeds the quantity supplied, which had been depressed past the lower price. In this state of affairs, eager gasoline buyers mob the gas stations, only to detect many stations running brusque of fuel. Oil companies and gas stations recognize that they accept an opportunity to make higher profits by selling what gasoline they accept at a higher price. Equally a result, the price rises toward the equilibrium level. Read Demand, Supply, and Efficiency for more discussion on the importance of the demand and supply model.

Fundamental Concepts and Summary

A demand schedule is a table that shows the quantity demanded at different prices in the market. A demand curve shows the relationship between quantity demanded and price in a given market on a graph. The constabulary of demand states that a higher price typically leads to a lower quantity demanded.

A supply schedule is a table that shows the quantity supplied at dissimilar prices in the market. A supply bend shows the human relationship between quantity supplied and toll on a graph. The law of supply says that a college price typically leads to a higher quantity supplied.

The equilibrium toll and equilibrium quantity occur where the supply and demand curves cross. The equilibrium occurs where the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied. If the price is below the equilibrium level, then the quantity demanded will exceed the quantity supplied. Excess demand or a shortage will exist. If the price is above the equilibrium level, so the quantity supplied will exceed the quantity demanded. Excess supply or a surplus will exist. In either instance, economic pressures will push the toll toward the equilibrium level.

Self-Check Questions

Review Effigy 3. Suppose the cost of gasoline is $1.60 per gallon. Is the quantity demanded college or lower than at the equilibrium price of $1.40 per gallon? And what about the quantity supplied? Is there a shortage or a surplus in the market? If so, of how much?

Review Questions

- What determines the level of prices in a market place?

- What does a downward-sloping demand bend mean about how buyers in a market will react to a college toll?

- Volition demand curves accept the same exact shape in all markets? If non, how volition they differ?

- Volition supply curves have the aforementioned shape in all markets? If not, how will they differ?

- What is the relationship between quantity demanded and quantity supplied at equilibrium? What is the relationship when there is a shortage? What is the relationship when in that location is a surplus?

- How tin you locate the equilibrium point on a demand and supply graph?

- If the price is above the equilibrium level, would you predict a surplus or a shortage? If the cost is below the equilibrium level, would you predict a surplus or a shortage? Why?

- When the price is higher up the equilibrium, explicate how market forces move the market price to equilibrium. Practice the same when the toll is below the equilibrium.

- What is the difference between the need and the quantity demanded of a product, say milk? Explicate in words and show the difference on a graph with a demand curve for milk.

- What is the divergence betwixt the supply and the quantity supplied of a product, say milk? Explain in words and show the difference on a graph with the supply bend for milk.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Review Figure iii. Suppose the regime decided that, since gasoline is a necessity, its toll should be legally capped at $1.30 per gallon. What do you anticipate would be the event in the gasoline market?

- Explain why the following argument is faux: "In the goods market, no buyer would be willing to pay more than than the equilibrium price."

- Explain why the following statement is false: "In the goods market place, no seller would be willing to sell for less than the equilibrium toll."

Problems

Review Figure three once again. Suppose the price of gasoline is $1.00. Will the quantity demanded be lower or higher than at the equilibrium cost of $1.40 per gallon? Will the quantity supplied exist lower or college? Is in that location a shortage or a surplus in the market? If so, of how much?

References

Costanza, Robert, and Lisa Wainger. "No Bookkeeping For Nature: How Conventional Economic science Distorts the Value of Things." The Washington Mail. September 2, 1990.

European Commission: Agriculture and Rural Development. 2013. "Overview of the CAP Reform: 2014-2024." Accessed April xiii, 205. http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/cap-post-2013/.

Radford, R. A. "The Economic Organisation of a P.O.W. Campsite." Economica. no. 48 (1945): 189-201. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2550133.

Glossary

- need curve

- a graphic representation of the relationship between cost and quantity demanded of a sure good or service, with quantity on the horizontal axis and the price on the vertical axis

- need schedule

- a tabular array that shows a range of prices for a certain good or service and the quantity demanded at each toll

- demand

- the relationship between price and the quantity demanded of a certain expert or service

- equilibrium price

- the cost where quantity demanded is equal to quantity supplied

- equilibrium quantity

- the quantity at which quantity demanded and quantity supplied are equal for a certain price level

- equilibrium

- the situation where quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied; the combination of toll and quantity where in that location is no economic pressure from surpluses or shortages that would cause price or quantity to alter

- excess demand

- at the existing cost, the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied; likewise called a shortage

- excess supply

- at the existing cost, quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded; also called a surplus

- law of demand

- the common relationship that a higher price leads to a lower quantity demanded of a certain good or service and a lower price leads to a higher quantity demanded, while all other variables are held constant

- law of supply

- the common human relationship that a higher price leads to a greater quantity supplied and a lower price leads to a lower quantity supplied, while all other variables are held constant

- price

- what a buyer pays for a unit of the specific good or service

- quantity demanded

- the total number of units of a good or service consumers are willing to purchase at a given price

- quantity supplied

- the total number of units of a good or service producers are willing to sell at a given price

- shortage

- at the existing price, the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied; also called excess demand

- supply bend

- a line that shows the relationship between price and quantity supplied on a graph, with quantity supplied on the horizontal axis and price on the vertical axis

- supply schedule

- a table that shows a range of prices for a good or service and the quantity supplied at each cost

- supply

- the relationship between price and the quantity supplied of a certain good or service

- surplus

- at the existing cost, quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded; too called backlog supply

Solutions

Answers to Cocky-Cheque Questions

Since $1.sixty per gallon is above the equilibrium price, the quantity demanded would be lower at 550 gallons and the quantity supplied would be higher at 640 gallons. (These results are due to the laws of demand and supply, respectively.) The result of lower Qd and college Qs would be a surplus in the gasoline market of 640 – 550 = xc gallons.

armstronghade1968.blogspot.com

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/principlesofeconomics/chapter/3-1-demand-supply-and-equilibrium-in-markets-for-goods-and-services/